Curing cuts with cod: can fish skin grafts help heal horses’ wounds?

Dr. Alannah Friedlund (BSA’17, DVM’22) has gained firsthand experience treating all kinds of bloody, nasty cuts, gashes and slices on horses’ legs during her time at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM).

By Tyler Schroeder“We see a lot of horses with leg wounds coming into our clinic [WCVM Veterinary Medical Centre]. Owners can spend a lot of time cleaning wounds, bandaging wounds and then monitoring the wounds in the healing process,” says Friedlund, a resident in large animal surgery and graduate student at the University of Saskatchewan.

A common occurrence in horses of all ages, lower-limb wounds are challenging to treat and manage since they’re slow to heal and vulnerable to infection. Keen to find new treatment options for lower-limb wounds, Friedlund began investigating alternative wound therapy methods as part of her master’s program. What surprised her was the lack of peer-reviewed, published research about the use of these non-traditional therapies on equine wounds.

“I found that no one has ever investigated the efficacy of fish skin grafts in horses, particularly with lower-limb wounds,” says Friedlund, adding that alternative treatment methods aren’t very popular. “We don’t have a good biologic wound therapy that performs well enough to be worth the cost for owners.”

With financial support from the WCVM’s Townsend Equine Health Research Fund, Friedlund is conducting research on an unconventional approach for treating lower-limb wounds in horses: fish skin grafts.

Human physicians have successfully used fish skin grafts to treat burn victims and patients with chronic non-healing wounds. Now Friedlund and her graduate supervisor, Dr. Keri Thomas (DVM), want to find out if these promising results in human medicine will translate to practical use in equine health. Dr. Joe Bracamonte (DVM), an equine surgeon at the WCVM, is also part of the study.

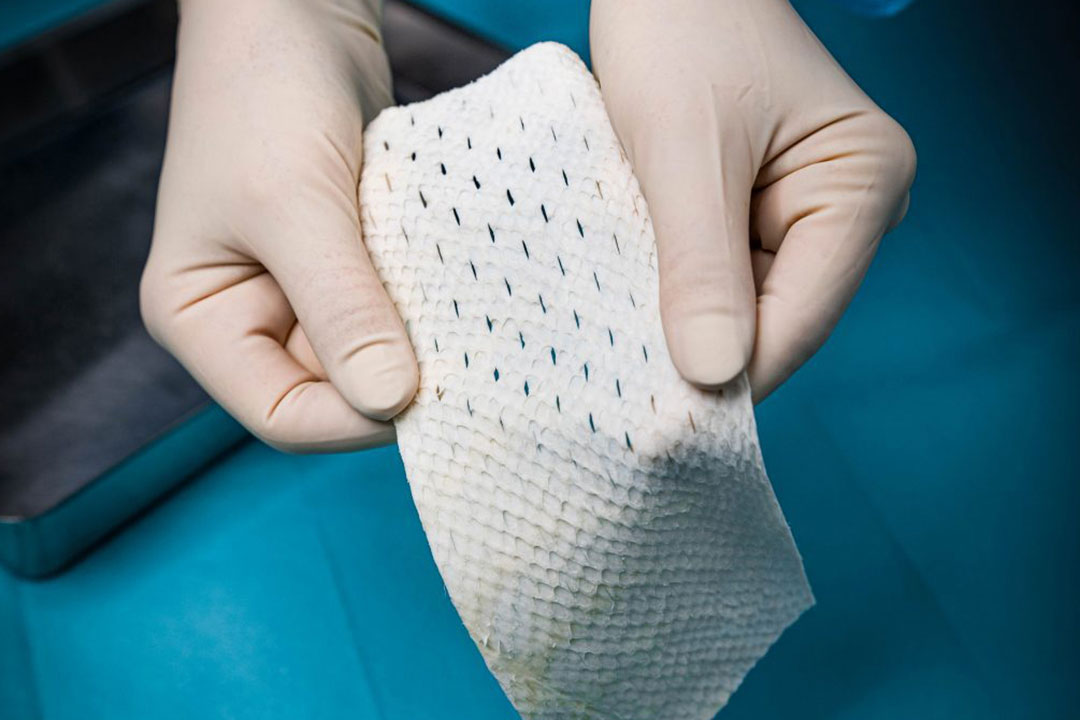

“The fish skin grafts that we’ll use in our study consist of a commercial product derived from Atlantic cod. We’re using a graft that’s already commercially available because if it proves to be effective, we want to know if it’s something that is actually feasible to start using in clinical practices,” says Friedlund.

The research team will make two small surgical wounds on each of the front lower limbs (mid-cannon bone) of eight horses participating in the study. Next, they will apply a fish skin graft to one wound and leave one wound without a graft on each front limb of each horse.

Over a three-week period, the researchers will monitor and document the healing process of each wound as they change the horses’ bandages. Using 3D wound management software, the research team can calculate precise measurements of the length, width, depth and surface area of the wounds as they progressively heal.

“We are interested in the microscopic properties of skin that can act as a graft for healthy skin cells to grow across,” says Friedlund. “There have been many bovine and porcine skin grafts used in the past, but those have a risk of disease transfer, so they have to be processed rigorously to decrease this risk for patients.”

Since fish don’t have any diseases that can be transferred to people or horses, fish skin grafts don’t have to be as highly processed — meaning that a larger amount of their desirable microscopic features are preserved.

In addition to accelerating skin growth, Friedlund points out that the grafts could provide other beneficial functions such as acting as a physical barrier against infection and bacterial contamination — an important factor for horses.

“Leg wounds in horses are often prone to contamination because they’re so close to the ground. We’re going to swab the wounds at three different times in the study to see if the grafts inhibit bacterial proliferation as they [the product’s manufacters] claim,” says Friedlund.

The fish skin grafts also show potential in stopping the growth of exuberant granulation tissue (proud flesh), which occurs during the healing of lower-limb wounds in horses. If there’s too much proud flesh at the wound site, this type of tissue can hinder the normal healing process.

Friedlund is optimistic that fish skin grafting could eventually become a viable treatment option for treating horses’ lower-limb wounds. She hopes that data gathered through her research study will help to better inform horse owners’ decisions on practical wound treatment options.

“If there’s a way that we can use these grafts to decrease the amount of time and stress involved in recovery, it would be very beneficial,” says Friedlund. “Not only for the horses, but for the people taking care of them, too.”

Article originally published at https://wcvmtoday.usask.ca

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.