Bringing more technology to ranch country

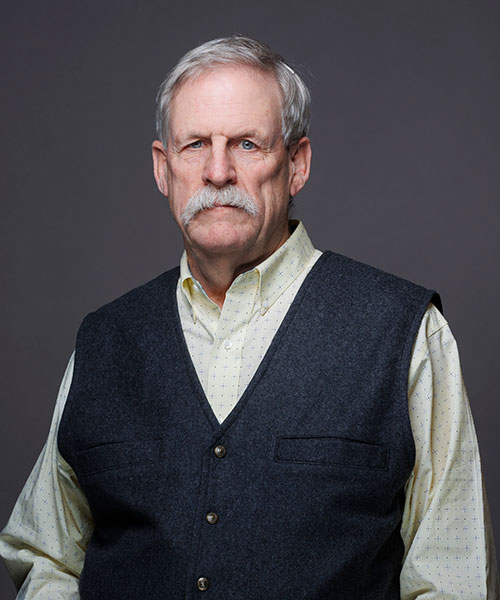

Seasoned USask researcher believes more genomics intelligence would greatly benefit cow-calf producers.

By Joanne PaulsonWhen cow-calf producers head out to buy a young bull at auction — an animal crucial to the herd’s success for years to come — they really don’t know what they’re getting.

Knowing the bull’s genomic information is critically important because, on average, 75 per cent of a calf crop’s genetics come from bulls used in the last two generations, 50 per cent from the current sire, and 25 per cent from the maternal grandsire.

Dr. Bart Lardner (BSA'91, MSc'93, PhD'98) thinks it’s time to apply better technology so producers can make informed decisions about the future of their herds.

“For years, they’ve made that decision based on visual assessment,” said Lardner, the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture Strategic Research Program Chair in Cow-Calf and Forage Systems, in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources at the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

“Producers go in the back and visually assess the bulls on offer, kick the tires, check out feet and legs, girth, all kinds of things they look at.”

But that hardly guarantees a reproductively sound young bull once relocated to the farm or ranch.

“You look at the animal, he looks good, but you bring him home and he’s a dud.”

Lardner is hoping to improve the selection process by building on a genetic evaluation tool called the Expected Progeny Difference (EPD), which compares the heritable efficiency or genetic worth of a sire to pass onto its calves within or across breeds, for traits of economic importance.

EPDs, which have been around for decades, are calculated by collecting performance data such as weights at birth, weaning and one year of age; daily feed intake and carcass quality; and fertility records like heifer pregnancy rate, calving ease and stay-ability, or retention in the herd. The on-farm information is sent to breed associations, which develop the EPDs for that breed and individual EPDs for the sires.

In the last decade or so, genomic or marker information from the DNA of older sires has also been added to the EPD program, and these profiles are known as genomically-enhanced EPDs (GE-EPDs).

“We have EPDs for older animals,” Lardner explained. “A 10-year-old bull, for example, will have an EPD for a trait and it will be highly accurate because he’s had several calf crops. But when we purchase a yearling bull today, he’s unproven. We don’t know how he is going to work out back at the farm or the ranch for breeding.”

Adding to the dynamic beef genomics research already happening at USask, Lardner’s vision is to design a research study to help commercial cow-calf producers make better-informed purchasing decisions.

Looking at the EPDs of sires, the proposed study will follow their calf crops through birth, weaning, feeding and fodder for both bull calves and replacement heifers and then correlate those performance indicators with the sire’s GE-EPD for that trait.

“We’re going to measure how the calf performs from birth to slaughter or to replacement female, measure those traits related to production or fertility, and go back to look at how was that trait documented or recorded and was the expression of the trait in the progeny related to the sire GE-EPD for that trait,” Lardner said.

As a beef cattle research scientist focused on ways to apply technologies that can streamline farming practices, Lardner sees this study as a validation to help beef producers corner the market. Integration of this powerful genomic technology can open doors for commercial producers to be more aggressive and confident in selecting the right bulls and females to go back into the herd.

“If we use GE-EPD technology when deciding to buy those sires, we can be confident that those bulls are going to produce a really good calf crop that will express those traits of economic performance phenotypically,” Lardner said.

Lardner’s vision incorporates a strong commitment to sustainability, with a commitment to improved production and reduced costs and impact on the environment.

“Whether it’s the cropping or livestock industry, producers are committed to mitigating or minimizing any negative impact on the environment,” he said. “Specific examples could be nutrients released into the environment, excessive feed to sustain an animal, excess use of fossil fuels, or inefficient infrastructures to raise those animals. If we use GE-EPD information to select those sires, will we actually require fewer resources to raise those superior calves?”

The economics

The economics of the industry comprise a vital part of Lardner’s proposed research, which he sees as a multi-year study performed at four locations across Western Canada.

“We will evaluate these animal traits, determine if they are associated with positive outcomes, and quantify the costs and benefits to the cow-calf producer,” Lardner said.

Commercial beef producers obviously must see a return on investment, he added, and it’s particularly crucial in today’s market. Many cannot afford to buy the expensive proven bulls, so they must choose from the lower-priced younger and unproven animals at a bull sale. Then the heat of the moment comes into play.

“A rancher might study the bull in the sale barn prior to the sale, but once that sale gets going, you’re competing with the other buyers,” he said.

“You might pay a few thousand dollars more than what you thought was your final bid, because you don’t want to lose the opportunity to buy that bull.”

Armed with genomic information, beef cattle producers may be able to answer questions about a particular animal ahead of time and assign an economic value, based on their objectives.

“Where do I want to see these animals in five years? Where do I want to see them in 10 years? Do I want to have calves that hit the feed yard and do well? Do I want to have good weaning weights because I want to sell them?” Lardner said, listing some of the potential producers’ expected outcomes from a breeding program.

But at present, “There’s no data that shows if the cow-calf producer purchased that low-genetic merit sire using GE-EPD, how the calf is going to perform. It just doesn’t exist.”

Going public

Lardner is constantly speaking, travelling, giving webinars, and otherwise spreading information to the beef industry. Once this study is done, he will do the same with the information gleaned.

“And it will come out in knowledge nuggets, fact sheets or social media posts to get the message to the commercial beef producer stating, ‘don’t be scared of using genomic tools when you make these bull purchases. Understand them so you have confidence when you go to buy that sire.’”

This study will give ranchers and farmers the grit and the fortitude to deal with really challenging circumstances similar to drought or low prices or any number of other challenges.

The importance of knowledge also goes up the supply chain to feedlots and packing plants, which seek uniformity among animals because these sectors also want to supply and sell consistent products. However, any improvement in weaning weight is the primary area where commercial operations can capture benefits from superior sires. Understanding a calf crop’s post-weaning genetic potential for feedlot and carcass performance is invaluable information for buyers.

“If we don’t use this genetic information, this technological tool, we’re going to continue to produce the smorgasbord of variance in different calf-performance indices,” Lardner said. “We have wide diversity of cattle in the backgrounding lots and feedlots, and we see inconsistency in the variance of performance.

“It boils down to the primary or commercial cow-calf producer,” he said. “How is he making those decisions? We have the technology today, and let’s consider integrating it when we make that decision to purchase an animal that will have multiple down-stream effects.”

Article originally published at https://news.usask.ca

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.