A commitment to life-long learning

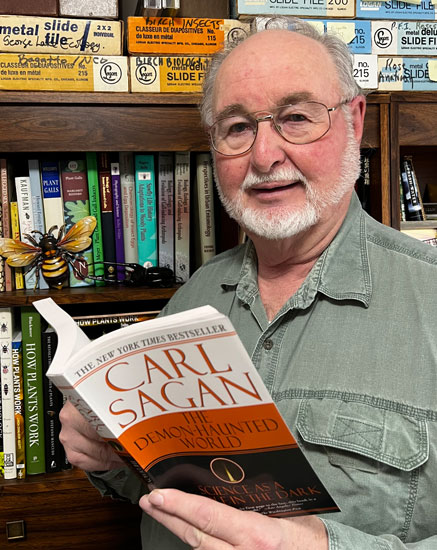

Retired entomologist Dr. Joe D. Shorthouse (PhD’75), who spent much of his career studying gall-inducing insects on wild roses, continues to pursue his passion for scientific discovery and storytelling

By Shannon Boklaschuk

University of Saskatchewan (USask) graduate Dr. Joe D. Shorthouse (PhD’75) got his start in entomology—the scientific study of insects—while growing up in Lethbridge, Alberta.

As an elementary school student in 1958, Shorthouse joined a science club for youth hosted by USask alumna Dr. Ruby I. Larson (BA’42, MA’45, PhD). The Junior Science Club of Lethbridge, which included 16 boys from Shorthouse’s neighbourhood, proved to be a formative experience for the children. Shorthouse enthusiastically began studying insects with Larson—who was, at the time, a wheat geneticist at the Lethbridge Research Station of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada—and scientific research soon became his passion.

“She started this club for just average blue-collar neighbourhood kids and turned her basement into a research lab,” he said.

At the age of 12, Shorthouse began studying galls, the ball-like masses that form on wild roses when tiny cynipid wasps lay eggs on the plants. Shorthouse recalls asking Larson some questions about the galls, and when she said, “no one knows the answers,” the hairs on the back of his neck stood up. It was then that he knew his future was in science.

“She said, ‘If you want, you could spend the rest of your life trying to come up with the answers,’ ” said Shorthouse. “There were 16 boys in that club. Many of them got PhDs. Three did their doctoral dissertations on the insects they learned about when they were in that club. The things they studied when they were 12 to 16 years old ended up being the subjects of their PhD —I’m one of them.”

For Shorthouse, Larson’s mentorship continues to exemplify the importance of scientists sharing their knowledge with others and the impact that adults can have when they spend time with children and encourage their curiosity.

After graduating from high school, Shorthouse studied biology at the University of Alberta for his Bachelor of Science (BSc) and Master of Science (MSc) degrees. Near the end of his MSc, a professor advised him to study the plant side of galls as well as the insects and said such a multi-disciplinary education could be found at USask. Shorthouse was also advised to contact Dr. Taylor A. Steeves (PhD) at USask’s Department of Biology. He did, and then moved to Saskatoon during the summer of 1970 to begin his doctoral studies on rose galls.

“Taylor Steeves, at the time, was one of the top four plant morphologists in the world,” said Shorthouse. “He agreed to be on my supervisory committee to help me look at the botanical side of rose galls and that I continued doing so until my retirement in 2013.”

Shorthouse credits Steeves with helping him to the see “the big picture” of biology by encouraging him to study both plant and insect development. Shorthouse’s PhD supervisor, Dr. Dennis Lehmkuhl (PhD), also encouraged him to take “a multi-disciplinary approach” to his doctoral research and to consider how ecosystems work, Shorthouse said.

“Dennis Lehmkuhl studied aquatic ecosystems. I’m not an aquatic biologist and I was his first PhD student,” said Shorthouse, who later went on to become a faculty member in biology at Laurentian University in Sudbury, Ontario. Shorthouse brought the interdisciplinary approach he saw at USask into his own post-secondary teaching.

“I tried to instill the culture that I learned there in my own students and my own department,” he said. “I succeeded sometimes, failed others, but it was always fun trying.”

One of the highlights of Shorthouse’s time at USask was earning a “Musk-Ox scholarship” through the university’s former Institute for Northern Studies. The scholarship funded a month-long trip to Alaska and the Yukon in 1971 to sample northern roses and galls.

“It was very important for me,” said Shorthouse, who recently wrote about the trip in an article titled “Romancing the wild shrub rose in Northwestern Canada by storytelling” that was published in June 2024 in the Bulletin of the Entomological Society of Canada.

While on the expedition, supported by USask, Shorthouse and his wife, Marilyn, recall sitting on the front porch of writer and poet Robert Service’s cabin in Dawson City. Shorthouse remembers looking down and seeing gold-coloured galls of the cynipid gall wasps he was looking for, on a wild rose in the cabin’s front yard. It was a magical moment, and Shorthouse wrote an article about the trip for The Beaver magazine as soon as they returned to Saskatoon. “That was over half a century ago,” he said.

Today, almost 50 years since Shorthouse completed his doctoral degree at USask, he continues to be a proud alumnus. He recalls his USask Convocation ceremony in 1975, when he received his degree from former Prime Minister John G. Diefenbaker, a fellow USask graduate.

After completing his PhD, Shorthouse began a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Postdoctoral Fellowship with Agriculture Canada in Regina, researching the biological control of weeds with gall-inducing insects. He accepted a position at Laurentian University in Sudbury in 1975, where he was promoted to associate professor in 1980 and to full professor in 1990. At Laurentian, as he had at USask, Shorthouse continued his research on plant-feeding insects—particularly those inducing galls on the wild roses of Canada—and also became interested in the insect diversity on Manitoulin Island.

Shorthouse remembers moving to Ontario with Marilyn and their two young children in 1975. They were shocked to see the environmental damage in Sudbury—the air often smelled of sulfur dioxide at the time—due to mining and smelting in the area. He quicky knew that he wanted to help contribute to the environmental revival of Sudbury and found the “holistic view” of biology that he developed at USask to be of great value in rebuilding ecosystems.

“I got (to be) part of a team (looking at) how to build forests on smelter-damaged lands. Using the holistic approach learned in Saskatchewan helped me play a role in what was to become the world’s most successful restoration project,” he said. “Industry, government, and academia came together to solve problems caused by acid precipitation and smelter emissions. Today the air is pure, the infamous superstack has been decommissioned, and healthy forests thrive on once blackened hilltops.”

Shorthouse retired from Laurentian University 13 years ago, but he isn’t slowing down. He still enjoys giving public presentations on roses, lilacs, lowbush blueberry shrubs, and the appearance of forests on the once industrially damaged lands around Sudbury. He is a Fellow of the Entomological Society of Canada, a professor emeritus, and is often called upon for media interviews. He is dedicated to knowledge dissemination and to writing articles and sharing stories about science that resonate with diverse audiences. He is a regular contributor to The Sudbury Star and The Manitoulin Expositor newspapers, penning articles on topics ranging from dandelions to monarch butterflies of Manitoulin Island to water quality in the Great Lakes. He has written 16 front-page feature articles for The Sudbury Star and more than 50 articles for the weekly newspaper The Manitoulin Expositor.

Throughout his university teaching career, Shorthouse was committed to employing storytelling in his lectures—often drawing from his own experiences as a doctoral student at USask. He believes storytelling helps people understand scientific concepts by making the information more personal and accessible.

“I recall my professors, particularly in entomology at the University of Alberta, coming back from conferences or international field trips and we couldn’t wait to sit around and hear what they had to say—and they were basically telling stories about what happened to them personally. And I remember perking up in lectures when the professors talked about something that personally happened to them,” Shorthouse said. “I have read academic articles on this with data to show that the level of learning with storytelling is enhanced.”

Shorthouse continues to hone his storytelling skills through his public presentations, the articles he writes, and the work he does in his community. He also advises new university faculty members to “pay attention and watch what happens when you include personal stories.”

“Get off topic, every once in a while, and tell a story related to what you’re lecturing about. It takes a lot of work and a lot of practice, but it’s such a lot of fun. And then to see the reaction of the students—no one falls asleep when you start a story,” Shorthouse said. “Storytelling is a critically important part of our university education.”

Shorthouse feels fortunate to have worked with and to have been inspired by scientists and educators such as Larson, Lehmkuhl, and Steeves—all whom had significant impacts on his life and scientific career. He advocates for mentorship, knowledge sharing, and public storytelling. In his June 2024 article in the Bulletin of the Entomological Society of Canada, for example, Shorthouse noted that “entomologists, indeed all biologists, should engage in public storytelling as often as they can.”

“It is the duty of entomologists to educate others about the world of insects and in doing so, try and include stories with a personal slant,” he wrote, adding that “telling entertaining stories about insects to all types of audiences is not only gratifying, but there is always the possibility that the stories will inspire someone to pursue a career in our science.”

Just like a youth club in Lethbridge once inspired its young members to become Canadian scientists who continue to make a difference today.