The science of business

By fusing together chemistry, biology, medicine, sustainability and business, Dr. Monique Simair (BSc’04, PhD’09) is a jack-of-all-trades when it comes to collaborative ways of thinking outside the box.

By ASHLEIGH MATTERNDavid Stobbe

On Dr. Monique Simair’s (BSc’04, PhD’09) first mine visit during a research fellowship in 2009, she was struck by the variety of expertise.

“A mine is like a tiny village of every expert you could possibly imagine,” said Simair. “From a plumber to an electrician to a geochemist to a geologist to a physicist. They’ve got everybody; it’s amazing.”

She asked questions about everything; acting as a sponge absorbing all the new information.

“It was an infinite amount of stuff I could learn about and find out what people do and what was interesting to them, and so I thought, this is a good fit for me—I can just point at things and ask questions and learn all the time,” said Simair.

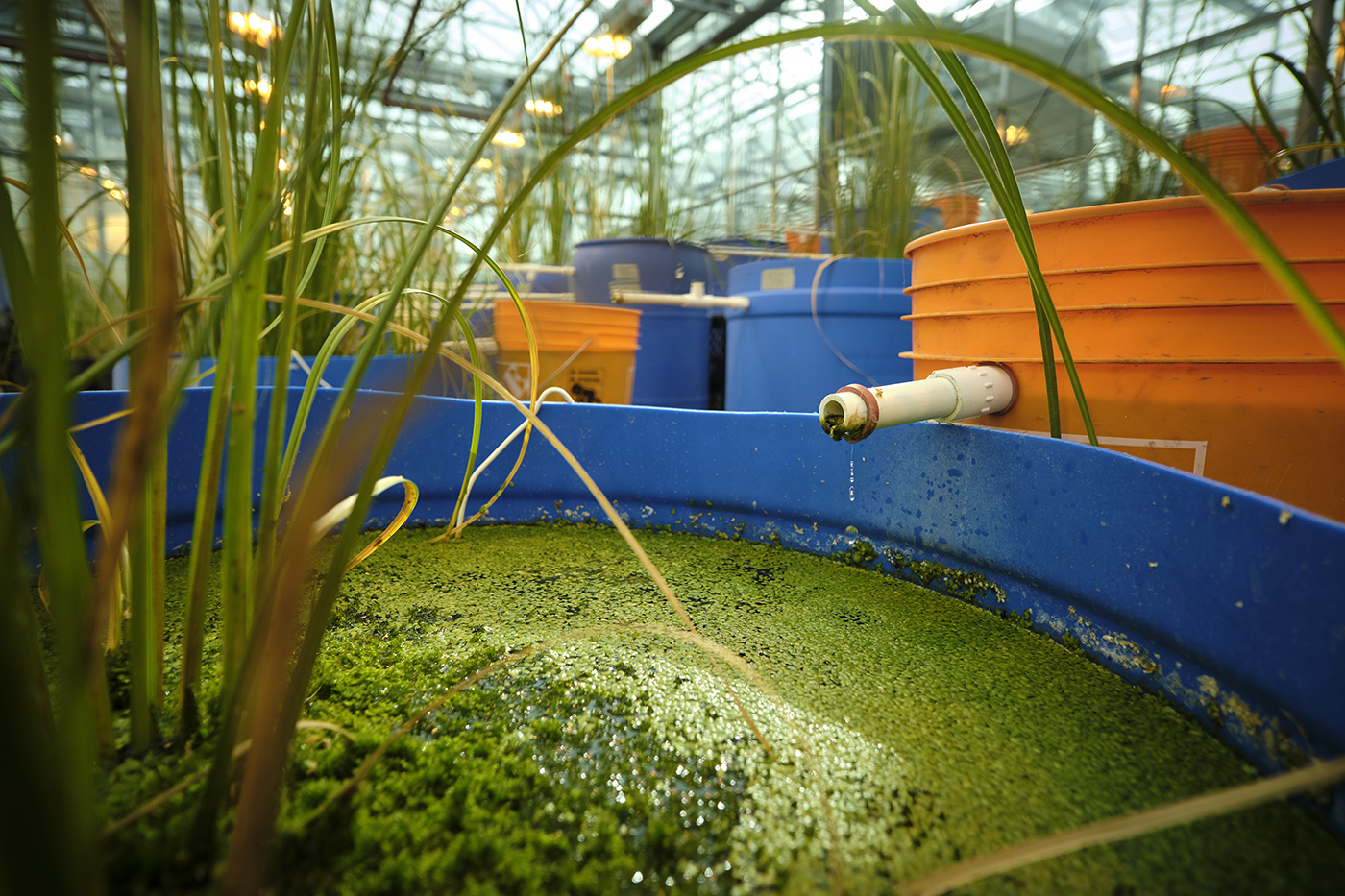

The experience had a big impact on the trajectory of her career. Simair founded Saskatoon-based Contango Strategies in 2010. The consulting, research and development firm uses groundbreaking genetic testing and microbiology labs to guide strategies for reducing the environmental impacts on water from the mining industry.

Collaboration is at the heart of her work. It all started with Simair’s idea to bring together multiple fields of study.

“The genetic work that we do started out in medicine with the microbiome analysis for human health,” Simair said.

“It was no easy feat to translate that technology to environmental work because it’s far more complex and challenging than the human body.”

The types of laboratories and pilot facilities Contango has are so rare in the industry that they have some of the major consulting firms from around North America contracting them to do work.

Their combination of biology and chemistry expertise is also rare in the water treatment sector.

“If you walk around [Contango], you’ll find there is a lot of young faces,” Simair said. “It’s a very young group largely because what we do here isn’t something that gets taught in university…. There’s no one type of training that will give you the combinations that we need, so we do a lot of teaching and training internally here with new graduates.”

And the industry is taking notice of this approach.

The Contango team’s treatment wetland project at the Minto Mine in the Yukon received a Robert Lemke award for excellence in environmental stewardship, outstanding social responsibility and leadership and innovation in the overall process.

A winding path to success

Simair’s path to starting Contango was anything but straightforward.

“I had no clue what I was going to do in school,” she said.

Before she went to university, she considered going into carpentry but her dad encouraged her to do carpentry for fun and get a university education. (She took him up on that, and a rocking chair she made sits in her office.)

At first, she thought she might go into medicine and took pre-med courses but she saw early on that wasn’t the path she wanted to take.

She did her undergraduate studies in medical microbiology and immunology, and did her PhD in applied microbiology in beer spoilage through the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at USask.

Simair said working on her PhD was one of her first experiences in collaboration. She was an outsider in the department, studying something that didn’t fit the usual mold. She had to explain to them why her work was important but she also needed to understand their viewpoint.

“There were so many interesting things that I was able to learn from all those people in lab medicine and apply over to what I was interested in,” she said.

Her PhD supervisor, Dr. Barry Ziola, also had a big impact on her.

“He really focused on teaching the skills and tools his students would need to be successful, not just in this field, but in life. You need to learn how to develop a budget. You need to learn how to write…. You need to learn how to work with other people. You need to learn how to sell because even an academic grant is a sale. You need to be able to explain to people why what you’re doing matters,” Simair said.

She then did two concurrent postdocs, one in bioprocessing and one in biogeochemistry. That’s when she says she fell in love with the mining sector.

After a short stint with a government job, she had the idea that would be the basis of Contango, drawing together her divergent expertise into the emerging field of biogeochemistry.

Dr. Reno Pontarollo (BSc’90, PhD’96, MBA’04), is the president and CEO of Genome Prairie, a non-profit organization that supports stakeholders in capturing and maximizing the benefits of research in genomics and related biosciences. He helped find funding to get the genomics technology off the ground at Contango.

At the time, the tests for environmental testing were pretty basic, Pontarollo said. “No one was using genomic approaches to assess samples.”

Pontarollo describes Simair as “a fireball,” saying he liked her eagerness, attitude and energy.

In his opinion, collaboration is necessary for success in business and research.

“All of the projects we develop at Genome Prairie are collaborations ... I can’t think of one standalone project,” he said.

“Through collaboration, both partners can access the expertise they need to succeed.”

The science of business

Simair said she didn’t know anything about business before she began Contango.

“If I had known better, I might have been smart enough to be terrified,” she said.

Today, business is her passion, and she’s found many similarities between business and science.

“Both have systems and processes. Both you have to understand what your fundamentals are that you’re working in… Once you learn what your working parameters are, you can work within it,” said Simair.

She describes business as “an ecosystem,” and draws comparisons to testing hypotheses in science, keeping track of the variables and controls so you can measure the outcomes.

“I believe in figuring out what works, not just what is conventional.”

This non-conventional approach to business has served her well. Simair was named one of Canada's future entrepreneurial leaders by Profit Magazine in 2011 and added to its W100 list of Canada's top female entrepreneurs in 2015.

Success in business isn’t new to the Simair family: Her siblings, Josh, Dan and Chris, started the popular food service app Skip the Dishes about two years after she started Contango. Even their parents have caught the entrepreneurial bug—Rod and Denyse Simair create and sell ceramic art.

The fact that all of the Simairs ended up running successful businesses isn’t something they planned for when they were growing up, she said.

“I don’t know if business per se is something that runs in the family, it’s more that we’re a bunch of geeks that aren’t afraid to really get into an idea and jump into something and give it our all,” she said.

How to collaborate

Simair sold Contango in June 2018 but stayed on for about a year as vice-president of technology and strategic initiatives. She announced her departure from the group in February 2019.

“I’m definitely a little bit terrified about moving on to something else ... but it’s also kind of exciting,” she said.

She’s started the process of building a new company called Maven Water & Environment.

“We’ll be working on revolutionizing the way water treatment is approached in the mining sector,” she said.

And she’s looking into building some philanthropic water treatment systems in other countries.

Collaboration is always at the heart of what she does.

She describes herself as “massively extroverted—to the point where I’ve had to work hard over the years to learn to listen.” But this extroversion has been a natural support in her networking, which is where she said collaborations often start.

“It’s all about finding people who have different viewpoints and ideas and ways of solving problems,” she said.

Applying collaboration and innovation to your own situation is like “trying to make friends in your 30s,” she said. “How do you meet people?"

“Don’t just expect it to happen. Come prepared. Be humble. Be more interested in them than your own stuff. And don’t go out there expecting everyone will want to collaborate with you; go out there trying to learn about interesting things.”

Whatever you do, don’t force it. She said forced collaborations tend to be short-lived.

“To find a lot of meaningful collaborations, it’s really about learning about others and trying to understand what drives and motivates them because then you can understand how their motivations fit into what you’re doing,” she said.

She notes that people are excited to talk about their work if you give them a chance, especially in academia. And if you see someone at the edges of a conversation or alone in a crowd, invite them in.

“A lot of the time it’s not only that you have to go searching for it, it’s that you’re not seeing that it’s searching for you already.”

Water security at USask

Collaboration needed now more than ever

Global freshwater security is at far greater risk than people realize, says hydrologist Dr. Jay Famiglietti, director of the Global Institute for Water Security at USask.

His article “Emerging Trends in Global Freshwater Availability,” published in Nature in May 2018, outlined some disturbing trends about the current state of water in the world.

“Our work with NASA satellites has revealed that the high- and low-latitude regions of the world are getting wetter and that the midlatitude regions in between are getting dryer,” Famiglietti said.

“We have also identified that over half of the world’s major groundwater aquifers are being rapidly depleted as a result of being overpumped to support irrigated agriculture. This puts food production, as well as water security, at considerable risk.”

At the same time, extreme flooding and drought are becoming more intense. All hope isn’t lost, though. International collaborations may yet save the day. Famiglietti said water plays a unique role in bringing people together.

“Shared water bodies are of mutual interest across political boundaries. Within countries, provinces and states, collaborations between governments, universities, civil society and the private sector will be essential to build cooperative networks and regional resilience.”