Code Orange

Providing care in response to tragedy

By Ashleigh MatternApril 6, 2018 is not a day anyone in Saskatchewan will soon forget.

Sixteen people died and 13 were injured in a collision between a bus carrying the Humboldt Broncos hockey team and a semi-trailer truck. The crash shook the entire Canadian hockey community and beyond.

Especially in Saskatchewan where hockey ties run so deep, most people remember where they were when they heard the news.

Heather Miazga (BSN'85) heard first through her husband, who had received a text from a fellow hockey dad.

There had been a crash, and it was looking like mass casualties.

“Almost as he was reading that out to me, I got the call,” Miazga recalls.

She is the director of surgical services for the Saskatchewan Health Authority, and was on call that week for any clinical leadership advice needed, but the call came from the emergency preparedness director.

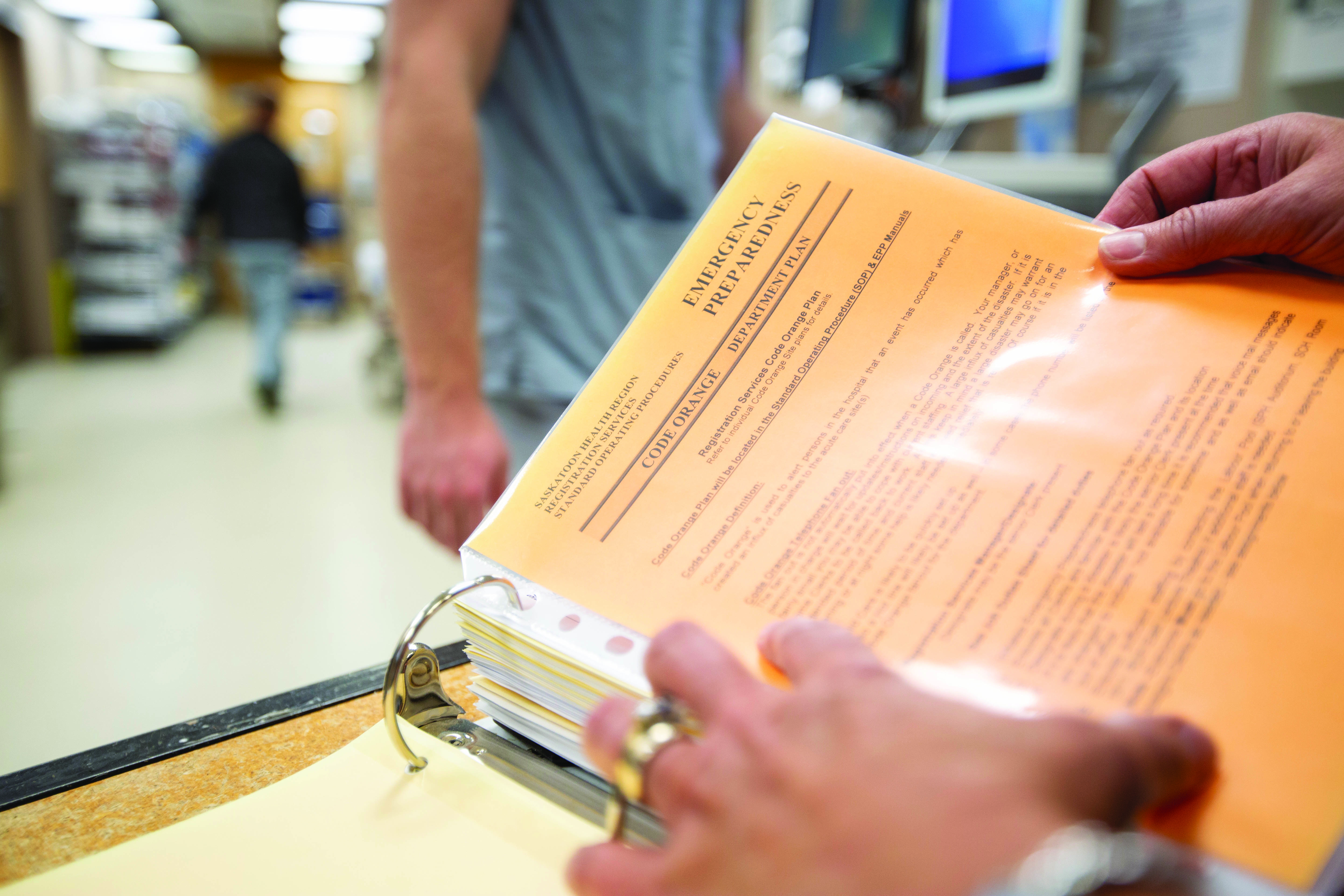

“The minute I landed… the charge nurse for the emergency department already had the emergency preparedness manual out,” Miazga said. “As I’m still getting my feet on the ground, they had already started thinking through the processes.”

Miazga and her family knew some of the people on the bus. Her oldest son had played for the Humboldt Broncos previously. Her younger son had played with some of the players as well.

“Saskatchewan is small,” she said. “We know the hockey world.”

But she had to put those emotional ties out of her mind to do her work.

“My background is critical care and emergency. Most of my career I’ve been involved in those areas and you need to be able to function at a high level and not be emotional about it and so I did just go into work mode and put that kind of on hold.”

All hands on deck Code Orange is a hospital emergency code that alerts staff to prepare for mass casualties. It’s incredibly rare; Miazga said Saskatchewan has never had a Code Orange to this magnitude.

But that doesn’t mean the hospitals weren’t ready.

Nipawin, Tisdale and Melfort were the nearest hospitals from the crash site and began to receive casualties between approximately five and six o’ clock that evening. From there, health- care providers stabilized the injured, who were then transported into Saskatoon's Royal University Hospital (RUH) for further treatment.

“It’s part of the work we do every day,” Miazga said. “Planning and emergency preparedness; there are several different emergency response codes—we look at occasionally done mock exercises that test different parts of our system.”

Miazga’s initial task was to work with the transport physician on indexing and triaging the incoming patients. It was 3:30 a.m. by the time they had made a plan to transport the last patient and the hard work was just beginning.

Ongoing work included critical health care for the patients, as well as supporting staff, families, extended families and billet families. All this, amongst a tsunami of emotion and public interest.

“The public interest in it was almost as challenging as the critical care and added a whole other workload that had to be managed,” Miazga said.

Even people with good intent, wanting to donate food, for example, created more work. Someone needed to manage that.

“It was a challenging but inspiring weekend to work through on many different levels… We all needed to do different jobs and support the team in different ways. The response to the call out when people were activating their Code Orange—it was astounding how people stepped up to the plate and responded.”

Every unit has a Code Orange plan, from the clinical units, to the dietary, to the laboratory, and beyond.

“Once that Code Orange is activated, each unit has a duty and a road map to start to follow,” said Miazga.

A Code Orange at one hospital also puts pressure on other health-care facilities; for example, patients had to be diverted to Saskatoon City Hospital Emergency to relieve pressure at RUH and St. Paul’s Hospital so they could deal with the most critical patients.

When plans go from paper into action, though, sometimes not everything goes as planned, and critical decision making needs to happen on the fly.

Miazga said the Code Orange worked like it was supposed to, but it also showed some areas for improvement; she said communication between the new provincial teams was one detail that could be focused on for the future.

Long-term impact

Scott Livingstone (BSP’88, MSC’94) is the CEO of the Saskatchewan Health Authority (SHA), and he said there have been a number of debriefs with teams, communities and stakeholders since the event to collect information and provide recommendations to improve the Code Orange response.

“Nothing is ever perfect and certainly with a Code Orange and mass casualty of this size, there are lots of things to learn,” Livingstone said.

He agreed that communication was a challenge, in part because the previous plans were all written in a time before social media played such a prominent role in our day-to-day lives. Information was coming in at a fast pace, including unconfirmed details through social media, making it a challenge to properly communicate about the changing situation.

The SHA as an organization had only existed for four months prior to the tragedy, having recently made the switch from 12 health regions to one provincial authority. However, the newly formed authority had launched with its emergency response systems intact.

“Seeing how different communities responded as a collective response even when so many different partners were involved, it’s reassuring to know our system was doing what it was supposed to do in these types of events,” said Livingstone.

He also praised the first responders in Melfort, Tisdale and Nipawin. In particular, Livingstone said at the Tisdale hospital, 70 staff responded in less than an hour.

“Their efforts were heroic and their stabilization of the people alive on the scene—the situation could be very different if not for their efforts. Our small community health care is alive and well in rural Saskatchewan,” Livingstone said.

He was notified of the collision immediately. He and others on the executive leadership team were tasked with making sure health-care providers on the ground had the resources they needed to perform their jobs.

Livingstone said it was “unprecedented” to have a Code Orange, and he’s proud of the work everyone did both that night and in the months since then.

“It was likely one of the most difficult nights of their career,” Livingstone said.

Dealing with catastrophic injuries and a large number of casualties can be a challenge despite the best training and experience, Livingstone said. Mental health and counselling support is in place for any staff members who are struggling to process the experience.

He expects the events that night will have a long-term impact not only on staff, but also on Good Samaritans and first responders at the scene, and, of course, the family members and friends of the athletes.

“A tragedy like this requires not only a healing of the body, but a healing of the mind for those directly involved, and care providers and mental-health professionals are working hard to care for those affected,” said Livingstone.

“Amazing families to stand alongside”

Dr. Joann Kawchuk (BSC’97, MD’01) said she was also grateful for the unstructured support that happens amongst staff.

“An arm around you behind a curtain, to shed a tear in a moment that you need,” she said. “It’s impossible at times to access support when you’re in the middle of those things, and it was apparent very early on that everyone needed to grieve.”

Kawchuk is currently the adult critical care department head. At the time of the tragedy, she was the most responsible physician for the intensive care unit (ICU) at RUH, managing the care for the sickest patients in the hospital.

She said everyone has a visceral reaction to tragedy, that “sinking, awful feeling,” we likely all know. But when you’re in a hospital setting, you put that immediate reaction aside and your role takes precedence. She calls that secondary feeling “anticipatory.”

“You’re constantly preparing and training yourself. It doesn’t fully prepare you, but you can certainly rely on those leadership skills and the team-based training you’ve done…

“It feels like rehearsal come to life. The lights are on; it’s time to show what we know.”

Kawchuk said everyone stepped up their game in order to execute Code Orange and take care of the patients’ intense needs, and she has a great deal of admiration for the people who came together to make the system work.

When she thinks of the tragedy, her strongest memories are from the days following that night, in the ICU. It was a situation completely out of the ordinary. She recalls one strange moment when she was doing her rounds as usual and turned around to see the prime minister standing behind her.

The tragedy eventually made international news, garnered celebrity attention, and raised over $15 million in a crowdfunding campaign, a national record.

But for Kawchuk and her team, they continued to stay focused and worked very closely with families to negotiate the next stages of life, or even passing. Despite the intense national and even international attention, they maintained intimacy for the families of their critically ill patients.

“I have made many gracious thank- yous to the families of people that I am lucky enough to look after when they’re in the ICU, including families specific to that time…. They were amazing families to stand alongside and share emotion alongside.”

What is Code Orange?

The Saskatchewan Health Authority (SHA) defines Code Orange as a call that initiates a hospital’s emergency response to a large number of incoming casualties.

The SHA says that while every Code Orange is unique, a basic emergency preparedness plan outlines what a facility’s response should be in a Code Orange situation.

Photos by David Stobbe

The road ahead

Like many people in Saskatchewan, Ivan English (BSc’97) was shocked to learn about the bus accident that claimed 16 lives on April 6.

“I was shocked at the number of injuries and how severe the crash was. You don’t ever want to hear anything like that, it was devastating,” said English.

English received his Bachelor of Science at the University of Saskatchewan and went on to the University of Toronto to study physical therapy. He works at the Saskatoon Rehabilitation Centre where he and a team of speech pathologists, social workers, occupational therapists, nurses and doctors work with patients after serious neurological injuries.

After hearing about the crash, English predicted many of the survivors would eventually make their way to the Rehabilitation Centre—which indeed many of them did after they were released from acute care.

“It didn’t take long to realize that some of them would be coming through a program like ours,” said English.

The road to recovery can be long, said English. He said one of the main factors in any patient’s success is if they are motivated to get better, something English saw in the injured players of the crash. Also, the amount of support that each one received was also an important part in adjusting after the tragedy.

“The goal is to try to help them get back to a better level of independence and quality of life,” said English. “The amount of support that they have had from their own families has been pretty amazing. I think support in general from the public as well. It’s been impressive and overwhelming,” said English.

Of course, some roads to recovery will be a longer road than others. The injuries range and therefore everyone’s recovery has been different. English maintains the main factors to recovery is the drive to succeed and support.

“Hopefully that will take them a long way. That’s one of the major things about getting them better… it’s a journey. This is the early part of physical rehab and then there’s a whole life to lead after this,” said English.

English and his team work with hundreds of patients every year. He watches them grow, adjust, change, strive and even struggle to adapt. He labels himself as “fortunate” because he is able to work with those who have made it and he is continually amazed by the willpower of those that come through his doors.

“You’re working with some of the most motivating people you’ve ever worked with. These guys in this accident but also most of our patients that go through a major injury are the strongest people I know,” said English.

“That’s one of the greatest things of working in this area. You see the best aspects of human nature. It’s pretty inspiring to work with.”