A testament of strength

Heather Kuttai (BA'94, MSC’09) was only six years old when a car accident took away her ability to walk.

By Henrytye Glazebrook

She doesn’t remember much more than flashes from the crash, both because of her young age and because of the trauma incurred when the vehicle came to a twisting, grinding halt. Still, there’s a kind of muscle-memory that has burned into her body even all these years later.

“I remember distinctly being really uncomfortable and lying on the side of the highway,” Kuttai said. “They dragged me out and laid me on a piece of cardboard. I remember how the asphalt felt under my fingers. I remember being very uncomfortable and scared, because I couldn’t feel my legs at that point.”

“It was a big car crash and people weren’t exactly listening to the six year old. They were trying to find my dad, who was working on the farm half a mile or so down the road.”

It’s been 42 years since that fateful night permanently put Kuttai in a wheelchair, but in the intervening time she has carved out a more than comfortable place in the world for herself. If you ask her directly, she’ll refer to herself professionally as a writer, human rights commissioner and disabilities activist. Between those words, you get a clear picture of her as a dedicated mother and warm friend.

What might be lost in that first impression, however, are the years that Kuttai spent among the finest athletes in the world, training tirelessly in pursuit of competition at the Paralympic Games and returning home with one bronze and two silver medals.

Kuttai’s introduction to target shooting came through her father, who saw his then 12-year-old daughter struggling to express herself athletically as she entered junior high. He brought her along to some of his own competitions, where she took aim alongside contestants her own age and discovered a natural love for the sport—even finding herself outpacing the able-bodied entrants in her purview, creating a rally for her to move into wheelchair sports despite her reticence. “I didn’t have any peers, I didn’t have any mentors and I did not see my disability as any kind of positive,” Kuttai said of the change into para-athletics. “It was a thing I tried to cover up and a thing I tried to pretend wasn’t there. I was so busy trying to be like everybody else that the concept of wheelchair sport was not only foreign, I wanted nothing to do with it.”

Kuttai’s father did what any good parent would do when faced with an immensely talented, yet stubborn, child: he bribed his daughter, convincing her with any means he had to chase her skill through to national competition in Calgary, Alta.

“I made the national team,” Kuttai said, recalling the moment that hobby transformed into ambition before her eyes. “I still didn’t want to be a part of any of it, and then the national coach called me up and said, ‘World championships are in a couple of months in California and I would like you to go.’

“I was 17 and there was an invitation to California, so I went.”

Feeding your ambitions

Colette Bourgonje (BSPE’84, BED’85) doesn’t have a specific moment when she knew she wanted to chase the Paralympics.

She likes to say that she got all the competitive genes in her family. Even when a car accident left her paraplegic at 18, it wasn’t long before the gravitational pull of athletics drew her into sit skiing.

“I just enjoyed competing,” Bourgonje recalls. “That really evolved into just being the best that I could be. I think initially it was competing against others, and now it’s more evolved into challenging myself and competing against myself.”

It’s this competitive spirit that has come to define Bourgonje’s life. First, she was a success story of someone who’d lost so much and still returned to the athletics she loved. Then she was the first ever student in a wheelchair to earn a bachelor's degree in physical education at the University of Saskatchewan. Later, she rode her stark determination to seven winter and three summer Paralympics, winning four bronze medals at the summer games and another three bronze and three silver at their winter counterpoint.

Each of these accomplishments are cherished memories for Bourgonje, but it’s her performance at the Vancouver 2010 Winter Games’ 10-kilometre sit ski race that holds a special place in her heart. The race marked the first time in Paralympic history that a Canadian medaled on home soil. To hear her tell the story, it’s clear that the race has etched a permanent, crystal-clear impression on her mind even to this day, despite a rocky start.

“I flipped the sled, actually,” Bourgonje said. “I was in the lead, and it was going great. I was probably in the best shape ever, really, but I was super aggressive — a little bit too aggressive—and made a little bit of an error on a downhill. I didn’t think I was going to make it. I thought if I did get anywhere, it might be a bronze.

“Getting up, my first thought was that I broke a ski or something. I don’t even remember the effort. There’s only a couple of times in your life where you're so focused and you feel unbelievably strong and I definitely pounded the rest of the 10K out."

Today, Bourgonje remains as active as ever even though she’s since retired from competition, seeking out young para-athletes to coach through a contract with the Saskatchewan Ski Association and training others at various levels—anything to leave her mark on the generation racing behind her, gaining ground each day.

“There’s a little guy in Canoe Lake who was in Grade 3 and couldn’t ski with his class because he has cerebral palsy,” she said of one of her proteges. “His feet wouldn’t stay in the boots and he wasn’t able to ski with his class, so he was crying. I took him a mountain board, which you can rest the sit ski on so you can train in the summer. He totally loved it.”

The next wave

It was someone just like Bourgonje and Kuttai—a Paralympian by the name of Ilana Dupont—who inspired Julian Nahachewsky (BCOMM’13, JD ‘17) to spring back from the accident that paralyzed him from the waist down.

Nahachewsky was “just a 19-year-old kid” when one wrong jump on his snowboard, too much air and a bad fall snapped his spine at his T-12 vertebrae. Only a month later, an invitation to visit the Cyclones Road and Track Club convinced him his life in sports wouldn’t change just because his means of participating had.

“A big part of learning to compete with a disability is seeing others and knowing where to set your standard and quality of life,” he said. “Through that club, I was able to see a whole bunch of really independent people live their lives. A paraplegic driving a full-size F350, getting in and out of that where some people might still be coddled—that was fundamental for me.”

Before long, wheelchair athletics grew into a passion. Describing himself as taking “part-time school in order to train full-time,” Nahachewsky started pushing himself to compete harder, racing nationally, internationally and even representing Canada at the 2013 paratriathlon world championships in London, England. In his spare time, he helped found a hand-cycling club and took up sit skiing to stay active in the winter months.

“Anybody still continuing to live life after a life-altering injury, it’s always good,” he said. “It shows human willpower. Obviously there are challenges that are traumatic that people deal with, but you see the people who are winners and who keep going—I think that’s a testament to our strength.”

It can be difficult these days for Nahachewsky to balance his love of racing with his burgeoning career as a lawyer with Miller Thompson LLP in Regina, SK. But whether he’s heading for mountains with his sit ski in tow or staying at the office late finishing paperwork, he’s always striving for excellence.

“Why not be some of the best at what you do?” Nahachewsky said. “Racing’s fun and it was a good group of people, but I just wanted to be the best. Even now, as a lawyer, I don’t want to be average. I want to be among the best.”

Beyond heroes or victims

It would be easy to say that it was the first time she sat in her wheelchair, the first time her dad handed her an air rifle, or that fateful trip to California that launched Kuttai toward her many staggering achievements. But listening to her speak, there’s no denying that there was always a champion spirit behind each and every accomplishment.

“I don’t know why we would want to live any other way,” Kuttai said. “We don’t get a lot of time as people, and I can’t imagine not trying to make a difference every day. It feels like a waste of a gift to not strive for something better.”

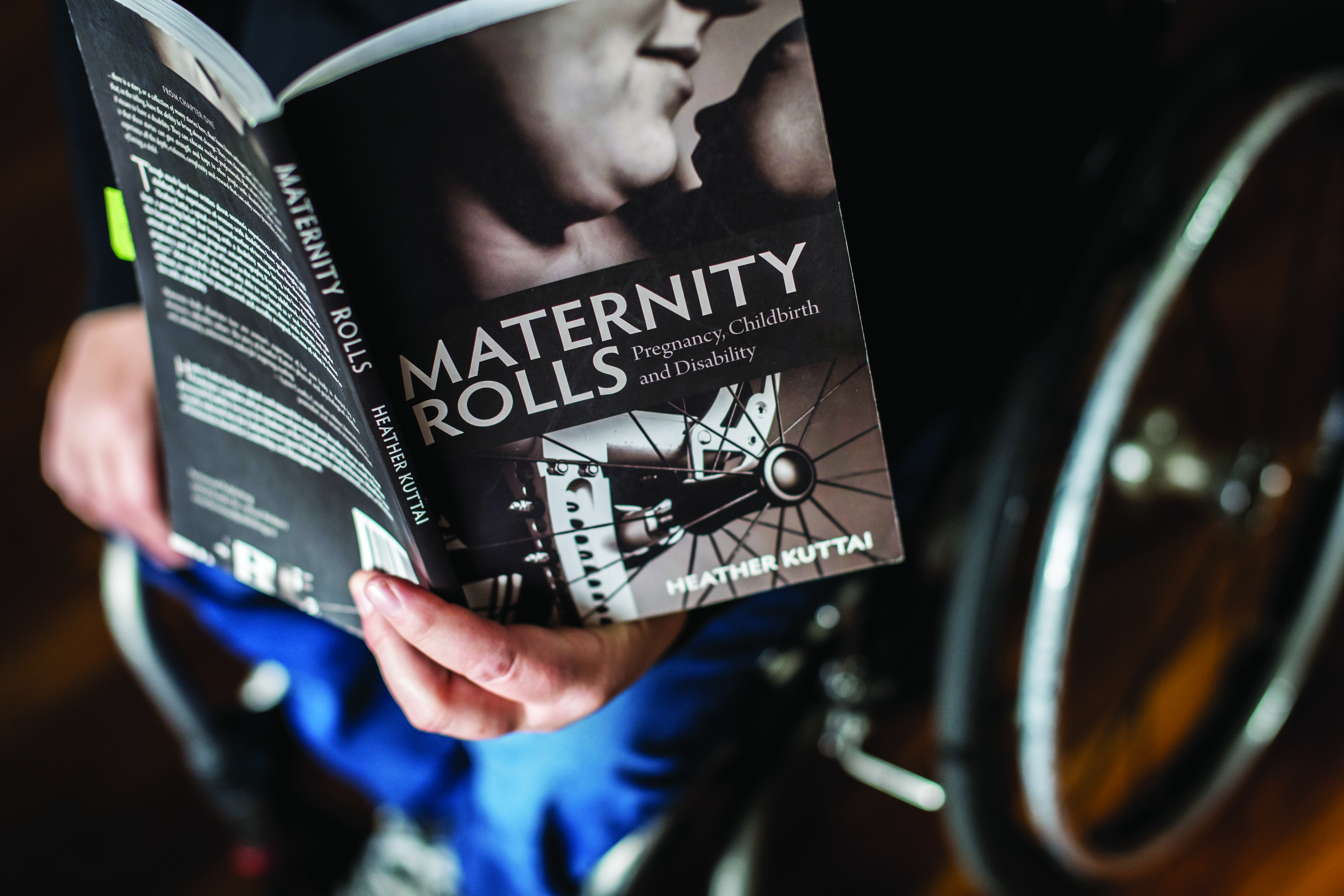

But even more critical to Kuttai is the importance of denying easy narratives. Hers is a life that skirted catastrophe far earlier than anyone would hope, sure, but it’s also one in which she’s made bold strides for herself and for others; pioneering the University of Saskatchewan’s Disabilities Services for Students and creating several retention programs, becoming a much sought after public speaker and recently authoring Maternity Rolls, a book detailing the unique experience of raising children as a paraplegic.

But all obstacles and achievements aside, Kuttai takes umbrage with her story, or that of anyone else with disabilities, being pushed into corners often reserved for superheroes and victims.

She’s just living life the only way she knows how.

“That word, ‘inspire,’ is a tricky one for me,” she said. “I don’t aspire to live as an inspiration. If I’m going to inspire anything, I hope it is to have people see that we are just regular people living regular lives and trying to do the best that we can in this world.

“I hope to inspire disability as an identity—as a positive identity, as an identity that fluctuates and that that’s okay. It’s okay to feel crappy about it some days and good about it others. It’s not an either- or kind of construct.”

Main photography by Lisa Landrie