The impact of Rossmo’s Formula

While working as a police officer, USask graduate Dr. Kim Rossmo (BA’78) developed a mathematical model to help locate serial criminals. His innovative work in criminology has since sparked diverse research in epidemiology, biology, the arts, and more.

By SHANNON BOKLASCHUKA world-renowned criminologist who pioneered the field of geographic profiling—an investigative technique used to help locate serial criminals—can trace the start of his influential career back to his formative years at the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

In the 1970s, Dr. Kim Rossmo (BA’78) began studying mathematics in USask’s College of Arts and Science. As a youth, Rossmo never had any doubt that he would one day attend USask; he was born and raised in Saskatoon, Sask., and long had his sights set on the university.

Rossmo initially enrolled at USask with a natural ability for math and physics, but a suggestion from a fellow USask student later resulted in him switching his major to sociology. The student—Rossmo’s girlfriend at the time—was studying psychology and encouraged him to take a vocational aptitude test, which revealed his affinity for investigations and his hunger for adventure. When she suggested criminology may be a possible field of study, Rossmo never looked back. He introduced himself to a criminologist in the College of Arts and Science’s Department of Sociology, Prof. Melanie Lautt, and then enrolled in her courses, going on to earn a Bachelor of Arts degree in sociology in 1978.

“I found it very interesting,” Rossmo said of sociology, in a recent interview with the Green&White. “It was hard for me at first, because it was totally different from math and physics, but I found it to be fascinating and I was interested in it, so that really made a difference.”

After graduating from USask, Rossmo joined the Vancouver Police Department—often walking the beat in the city’s “Skid Road.” While working as a police officer, he began attending graduate school at Simon Fraser University, completing both a master’s degree and a PhD in criminology—giving him the distinction of becoming Canada’s first police officer to earn a doctorate.

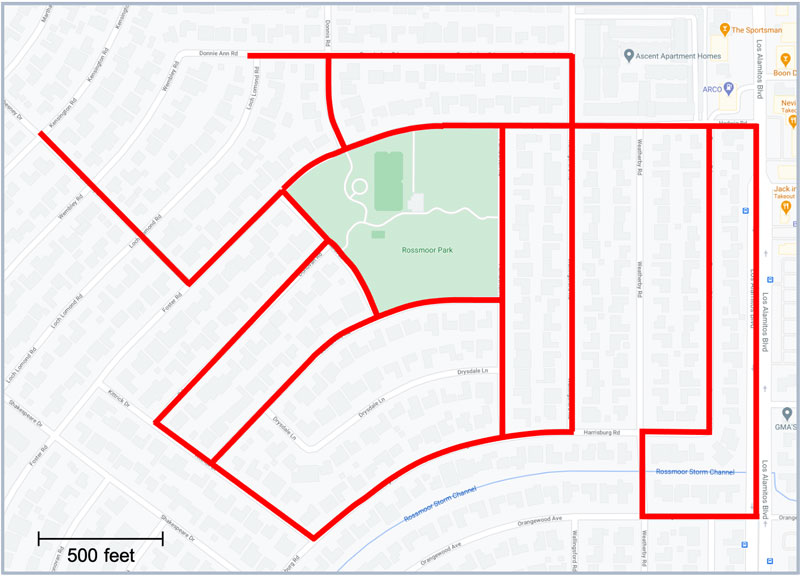

Rossmo’s groundbreaking PhD dissertation later led to the publication of an influential book, Geographic Profiling. The book, released in 2000, introduced a new technique to help locate serial killers and other repeat offenders by mapping the probability of their likely residences relative to their crime scenes.

“What geographic profiling does is it takes a look at the locations of a connected series of incidents—say murders in a serial murder case or robberies in a serial bank robbery case—and spatially analyzes the point pattern of incidents. It then creates a probability surface from these locations, working from the basis of an algorithm that says people offend close to where they live, but not too close,” Rossmo explained. “It generates probability surfaces for each crime site, then combines the different probability surfaces for all the crime sites and, in the end, you’re left with a colour map that focuses on where the offender most likely is based.”

Following his PhD dissertation, Rossmo became a rising star in the geography of crime, employing a mathematical formula—Rossmo’s Formula—that could be used to more efficiently find serial criminals. The formula was incorporated into a patented software system, which Rossmo named Rigel, to aid in police investigations.

“I’ve always believed that integrating the academic and the practical is a very important thing to pursue,” he said.

Rossmo went on to become the detective inspector in charge of the Vancouver Police Department’s Geographic Profiling Section and was awarded the Governor General of Canada Police Exemplary Service Medal.

Great white sharks, Jack the Ripper, and Banksy

Today, Rossmo is a full professor and the director of the Center for Geospatial Intelligence and Investigation in the School of Criminal Justice and Criminology at Texas State University, where he continues to research and publish in the areas of environmental criminology, the geography of crime, and criminal investigations. Although he now lives in the U.S., he maintains close ties to his hometown of Saskatoon and in 2009 was named one of the College of Arts and Science’s first 100 Alumni of Influence.

In the 25 years since Geographic Profiling was first published, Rossmo’s Formula, and its complex mathematical algorithm, has been used by the FBI, Scotland Yard, the RCMP, and the U.S. military to help locate criminal bases, including terrorist headquarters. Researchers and investigators have found many other useful applications for it, too, including in fraud and cybercrime cases. Rossmo enjoys seeing his work applied in new and creative ways.

“That, to me, is always exciting, because you’re exploring new tangents while still working on the stuff you originally focused on,” he said.

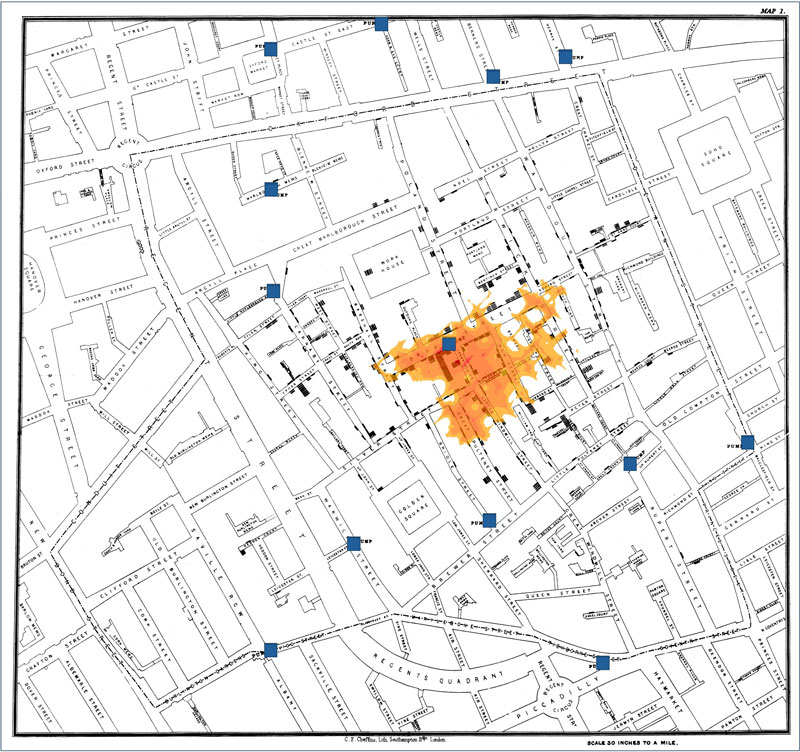

A quick Google search will reveal many fascinating articles about how Rossmo’s Formula has been applied by researchers around the world to diverse disciplines and topics far beyond crime and criminology—including using geographic profiling as a novel spatial tool in biology and zoology for targeting the control of invasive species. Geographic profiling techniques have also been employed by epidemiologists for various disease studies, including to examine a malaria outbreak in Cairo and to reconstruct an infamous historic 1854 cholera outbreak in Soho, London.

“I think this has a lot of promise,” said disease ecologist Richard Ostfeld, of the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, N.Y., in a 2011 article titled “Criminal-Profiling Trick Used to Combat Disease” published in Wired.

“It's a very interesting application of a criminological tool to epidemiology."

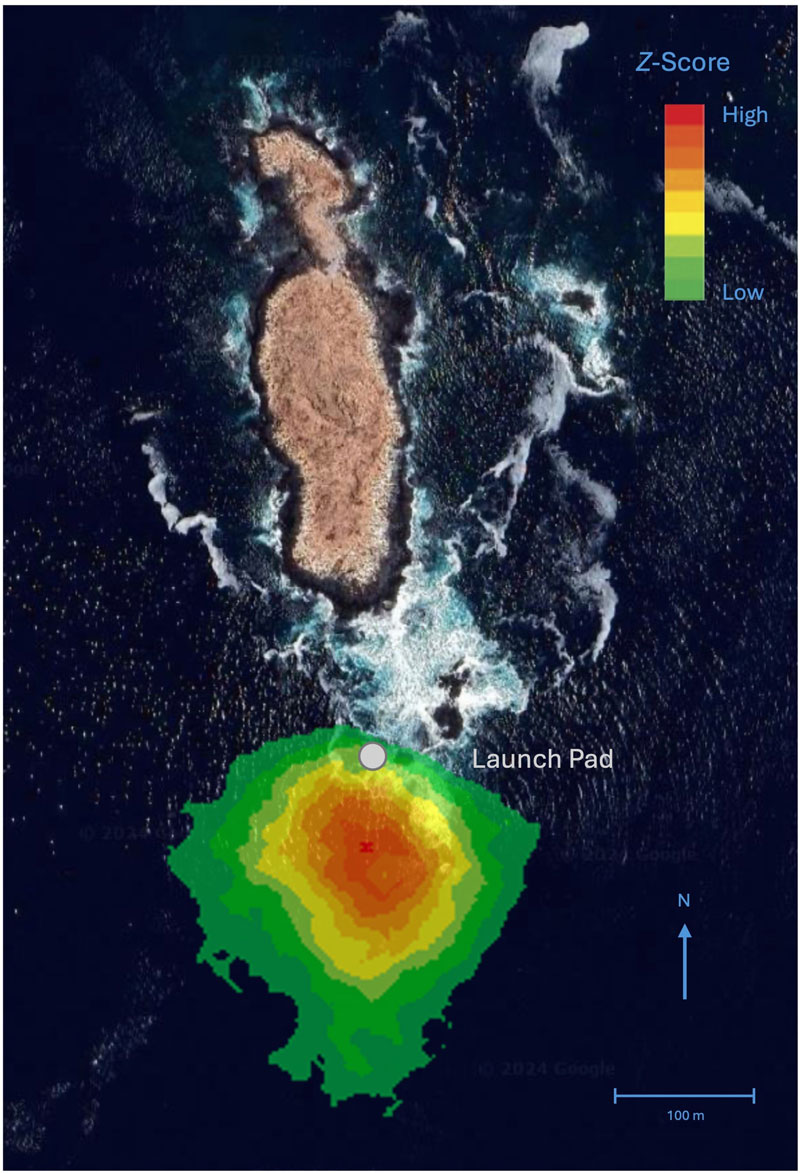

Rossmo’s Formula, through the use of the software Rigel, has also shown parallels between criminal behaviour and the hunting patterns of animal species. For a 2009 study, for example, Rossmo mapped how great white sharks pursue fur seals in False Bay near Cape Town, South Africa. The researchers learned that great white sharks—considered to be some of the fiercest predators on Earth—are similar to human serial killers in that they hunt in a highly focused fashion. As a result of the study, Rossmo appeared on television during the Discovery Channel’s Shark Week to talk about the shark-related findings.

“As it turned out, though, their attacks were not random,” he added. “There was a specific location that they kept returning to—sort of an optimal site from which to be starting their hunt for the seals.”

Geographic profiling has also been used to help shed light on one of the art world’s biggest questions. In a 2016 paper titled “Tagging Banksy: using geographic profiling to investigate a modern art mystery,” Rossmo and three colleagues at Queen Mary University in London, U.K., sought to test the validity of the notion that Bristol-born artist Robin Gunningham is, in fact, the famed street artist known as Banksy. While it hasn’t yet been proven that Gunningham is indeed Banksy, Rossmo’s work added more evidence to support the theory.

Although he is a self-described fan of Banksy’s work, Rossmo noted that not everyone was happy about the attempts to confirm Banksy’s identity.

“What was interesting was the reactions—some people were mortified that we had ‘outed’ Banksy,” he told the Green&White. “Well, the name Robert Gunningham had actually been in a major newspaper there, and we just said, ‘How does what we know about Gunningham fit him as a possible candidate?’ ”

While Banksy’s identity is still considered a modern-day mystery, Rossmo’s work has been used to try to solve historical mysteries as well—particularly the identity of Jack the Ripper, the infamous serial killer from Victorian England. Rossmo applied his mathematical model to try to find Jack the Ripper’s residence in London’s East End. His interest in the serial killer continued beyond that particular work. Later, Rossmo questioned a 2019 paper published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences that claimed to reveal the serial killer’s identity based on DNA evidence. In examining the claims, Rossmo pointed to probability errors, tunnel vision, a suspect-based focus, and confirmation bias—key topics that he also explored in his 2009 book, Criminal Investigative Failures.

“I’m looking at (the paper) and going, ‘There’s so many steps here, and each step has a certain probability of being correct or wrong, but they’re ignoring all those problems,’ ” he said. Rossmo’s commentary on the Journal of Forensic Sciences article was later published by the journal in 2019.

For years, investigative failures and wrongful convictions have been of deep interest to Rossmo, who in the 1990s suggested that a serial killer may be behind the disappearances of sex-trade workers from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Unfortunately, those warnings from Rossmo, who was then a geographical profiler with the Vancouver Police Department, were dismissed at the time—three years before the arrest of pig farmer and serial killer Robert Pickton in 2002. At an inquiry 10 years later, in 2012, Rossmo testified that he believed Pickton could have been caught more than two years earlier if the necessary resources had been dedicated toward the case.

In 2025, Rossmo continues to reflect on that case and that period of his career.

“I think there are a lot of lessons to be learned there, so let’s hope they have been,” he said. “But it was a very significant moment, in my career and others, because it showed how we can make mistakes even though no one wants to err.”

Geographic Profiling, 25 years later

With so much fascinating research undertaken with the application of Rossmo’s Formula over the past 25 years, Rossmo was recently encouraged by his editor to update Geographic Profiling. As a result, on April 1, 2025, the second edition of the book was released by Routledge, complete with new case studies that include the Golden State Killer, Operation Lynx, the Zodiac Killer, the Lindbergh baby kidnapping, the D.C. sniper attacks, and the Austin Midnight Assassin.

“The second edition of this book is long overdue,” Rossmo wrote in the book’s preface. “During the last quarter-century, there have been significant advancements in computer technology, geographic information systems, crime mapping, and police investigations. In turn, these developments have catalyzed studies in environmental criminology and studies of offender behavior. This edition brings together recent research and introduces a number of novel tactics and applications of geographic profiling that have emerged since 2000. Several case examples are used to illustrate principles and functions.”

The new edition also includes more than 100 colour photos, figures, and tables, and explores the application of geographic profiling to areas such as violent and property crime and counterterrorism/insurgency, as well as to what are more unexpected topics: earthquake epicentre and pirate base prediction, fruit flies, anthrax, bat foraging, and much more. Rossmo’s book also discusses investigative and criminal justice topics such as wrongful convictions, including the case of David Milgaard, the Canadian man who was wrongfully convicted of the sexual assault and murder of nursing student Gail Miller in Saskatoon and subsequently spent 23 years in prison.

“Geographic Profiling is a must‑have reference for detectives, crime analysts, and law enforcement officers who want to follow the geographic clues in their cases,” the book’s publisher notes. “Its clear presentation makes it ideal for college courses, police training, university scholars, and students of true crime.”

Zena Rossouw, a PhD student studying with Rossmo, is one of the many people who have been influenced and inspired by his work. Rossouw is originally from South Africa, but like Rossmo she completed her master’s degree at Simon Fraser University’s School of Criminology in British Columbia, where Rossmo continues to serve as an adjunct professor. Rossouw became interested in working with Rossmo after seeing him on television talking about the highly publicized case of Chandra Levy, a California intern at the Federal Bureau of Prisons in Washington, D.C., whose skeletal remains were found in 2002. Rossouw is now a doctoral student at Texas State University, where she uses Geographic Profiling as a handbook in her scholarly work.

“It is a gem,” she said in a recent interview with the Green&White.

One of the great aspects of Geographic Profiling is that the book is useful for scholars and researchers, but it is also accessible for people who may not be involved in academia but who are working in policing or the justice system in other ways, Rossouw added.

“There’re examples; there’re ideas. For investigators, there’re actual ideas—and they’re international and they apply,” she said. “What we know about violent crime is that, unfortunately, it transcends; it’s international.”

Rossouw has noticed how people around the world continually reach out to Rossmo for his expertise and advice. She appreciates and is in awe of his generosity of time, noting that he tries to respond to everyone who emails him. His work truly has “an international impact,” she said, as he is known as an innovator and a collaborator by researchers, investigators, and others across the globe.

“It’s really amazing to me that anything that I’m interested in he’s got a connection to, or he’s worked with someone in that field, in that country—so on and so forth,” said Rossouw.

Twenty-five years after its release, Rossmo is pleased that Geographic Profiling has been updated with new material to reflect the many technological and other advances that have occurred over that time. He is also happy that his ongoing work in geographic profiling continues to be useful to criminologists and others.

“It feels good, but then you always go, ‘All right, what now? What can I do next? How can we build on this?’ The last thing you want to do is rest on your laurels, and you need to keep pushing stuff forward. So that, to me, is always a major question,” he said.

“I’m constantly reminded, because of the requests I get, that there are real crime victims behind all this. And there are, on the other side of the equation, real injustices where innocent people are being arrested. So, you want to work to improve safety and security, and you want to work to improve justice.”