Take 5: Five original objects in the Museum of Antiquities

The USask museum, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, features full-scale replicas as well as original ancient glass, pottery, and coinage

The Museum of Antiquities at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) features a collection of Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and Near Eastern sculpture in full-scale replica, as well as original ancient glass, pottery, and coinage. The museum, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, is located in the Peter MacKinnon Building on the Saskatoon campus.

USask graduate Dr. Tracene Harvey (BA’98, MA’02), an expert in ancient Greek and Roman coins, serves as the director/curator of the museum. Harvey collaborated with fellow USask alumni and museum staff members Carrie Slager (BScKin’21), a numismatic researcher, and Cat Woloschuk (CTEJL’20, BA’21, MA’24), a museum intern, to choose five unique original objects that are housed in the Museum of Antiquities to showcase on the Green&White website.

1. Cypriot Bronze Age Oinochoe, Cyprus, c. 1800-1650 BCE

Cyprus can be regarded as a centre in which numerous ancient cultures have crossed paths, bringing into Cypriot art a number of artistic influences. Before the Greeks became known as experts in pottery decoration, Cyprus was in advance of the rest of the ancient world in this craft. Mycenaean influence can be seen in the geometric patterns they used, such as the latticework (resembling a basket) and zigzags found on this design. An oinochoe was a jug used primarily for serving wine.

2. Date Flask, Syro-Palestine, c. 50-150 CE

People in the ancient Mediterranean world loved cosmetics, including perfumes, and the most luxurious of perfumes were kept in glass vessels. The most common type of glass perfume bottle was the tubular unguentarium, but next-level luxury was a mold-blown vessel, in this case one in the form of a date, testament to one of the key ingredients of the unguent inside. Date-shaped vessels were one of the most popular perfume vessels.

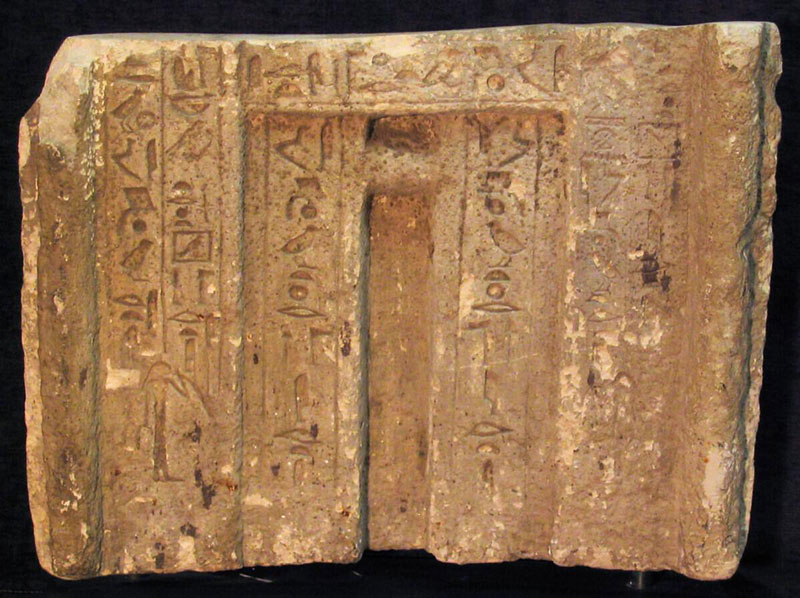

3. Egyptian False Door, Egypt, 2225-2175 BCE

This original false door from an Egyptian tomb is probably the most popular object in the museum’s collections and it is certainly the oldest, clocking in at more than 4,000 years old. This false door was once on the wall of the tomb of a priestess named Irti of the goddess Hathor. The so-called “false doors” are a common feature of Egyptian tombs of the Old and Middle Kingdoms (2780-2280 and 2134-1778 BC, respectively). The Egyptians believed that the afterlife was similar to the life of the living. For this reason, the dead too required food for sustenance. Offerings were supplied by the descendants of the deceased or by mortuary priests. It is believed that the primary function of false doors like this one was to offer the soul of the deceased access to this world to receive such offerings. They are called false doors because they do not open.

4. Bust of Hannibal, France, 17th Century CE

Hannibal Barca was a Carthaginian military commander who led forces against the Romans in Italy during the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE). He is best known for crossing the Alps with his forces, which included 37 war elephants, and successfully reaching and occupying Italy for 13 years. This bust is believed to have been made for King Louis XIV (r. 1643-1715) during the mid-17th century by either Francois Girardon, Louis’ sculptor, or his protégé, Sebastien Slodtz, but most likely made by the latter based on another one made by the former. This bust later made its way to Napoleon Bonaparte, who idolized Hannibal for his military prowess, where it was kept in the St. Cloud Chateau.

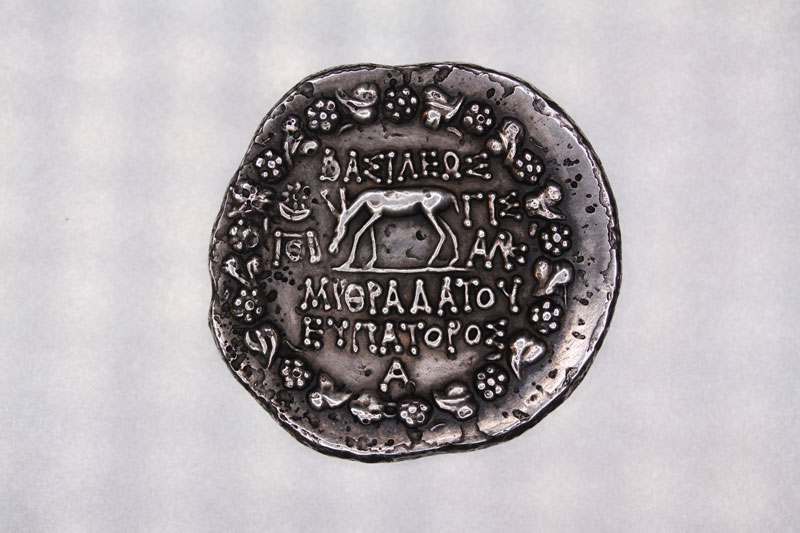

5. Silver Tetradrachm of Mithridates VI (r. 120-63 BCE), Kingdom of Pontus, 85 BCE

This coin is one of our favourites in the Museum of Antiquities’ collection for its beauty and level of detail. Mithradates VI, one of the last Hellenistic kings, imitates Alexander the Great in this portrait with his flowing hair and eyes turned toward the heavens. On the reverse, the stag and pinecone wreath are symbols of his devotion to his patron deity, Dionysus, Greek god of wine and theatre. The attention to detail on this coin shows that coins did not just serve a practical function in the ancient Mediterranean—they were also exquisite works of art.

The Museum of Antiquities is open to the public from 10 am to 4 pm Monday through Friday and from noon to 4 pm on Saturday. It is located in Room 106, Peter MacKinnon Building, 107 Administration Place, University of Saskatchewan. Admission is free, although donations are welcome. The museum is closed on long weekends and statutory holidays.