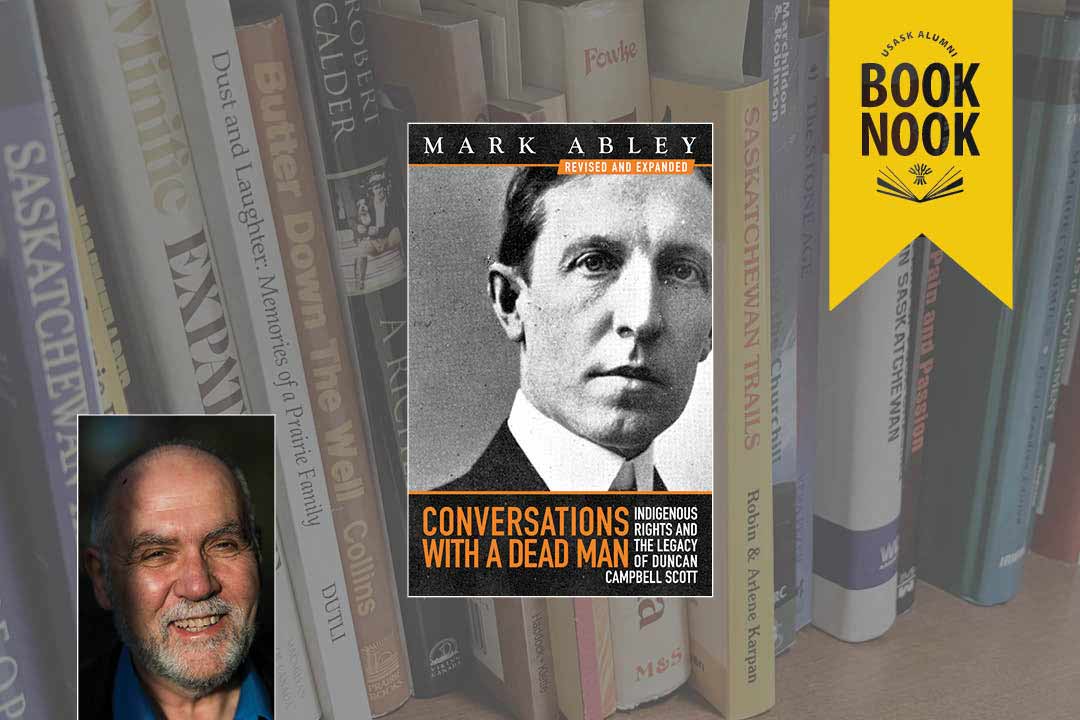

Alumni Book Nook: Dr. Mark Abley (BA’75, DLitt’22)

Mark Abley is the author of "Conversations with a Dead Man: Indigenous Rights and the Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott"

Award-winning Canadian author, journalist, poet, and editor Mark Abley (BA’75, DLitt’22), who was awarded an honorary Doctor of Letters degree during the University of Saskatchewan (USask) Fall Convocation celebrations in 2022, is the author of Conversations with a Dead Man: Indigenous Rights and the Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott. A graduate of USask’s College of Arts and Science, Abley’s previous books include Strange Bewildering Time (2023), The Organist (2019), The Tongues of Earth (2015), The Prodigal Tongue (2008), Spoken Here (2003), and Beyond Forget (1986).

Conversations with a Dead Man: Indigenous Rights and the Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott was first released in 2013. A revised and expanded version of the book, with a new introduction, was published in February 2024 by Stonehewer Books.

“While the book focuses on the life and work of Duncan Campbell Scott, poet and deputy minister of Indian Affairs, it also explores the much broader history of Indigenous-Canadian relations,” said Abley. “It shows aspects of history that many Canadians prefer to ignore—but it also suggests how far we have come.”

Abley was inspired to write Conversations with a Dead Man because of his “puzzlement as to how one of the best poets in early 20th-century Canada could have been responsible for overseeing so much injustice and inflicting so much pain.”

“We need to understand the past if we are to move forward,” he said. “I believe that reconciliation depends on truth.”

You have described your book as creative non-fiction. What can readers expect from a book in this genre, and from your book more specifically?

All good books involve the imagination, and I’m not wild about the term “creative nonfiction”—it seems to imply that many books of nonfiction are uncreative. But essentially, the way it has come to be used, “creative nonfiction” refers to writing that deploys some fictional elements to tell a factual story. In my book, all the details I provide about the life and work of Duncan Campbell Scott are true. But the conversations I have with his ghost are fictional. I hope the form allows readers to feel more engaged with the subject than they would in a standard biography. I want readers to grapple, as I did, with a question at the heart of the book: how could an intelligent, loyal, and imaginative poet also be the civil servant responsible for overseeing and expanding the residential school system, and for imprisoning people who dared to continue practicing the sun dance and the potlatch?

Why did you want to explore the history of Indigenous-settler relations in Canada?

I grew up in Saskatoon knowing almost nothing about Indigenous history—and, more shamefully, caring very little. Eventually I came to realize the shallowness of my understanding. In recent decades, people in the mainstream of Canadian society have begun to learn—or been forced to learn—much more about the failures of colonialism, and how the terrible wounds inflicted by colonialism still affect us all. Conversations with a Dead Man is my attempt to contribute to that learning process.

What was it like to research this book? What sources and materials did you explore?

The research was fascinating—I loved it! I read some of Duncan Campbell Scott’s letters in the National Archives. I worked in other archives in Montreal, Toronto, and Kingston. I did a lot of research online. And I read some really obscure books and magazines. The Alberta historian Donald B. Smith was a tremendous help to me; I am forever in his debt. Thanks to a Montreal friend, I even met an elderly couple in Ottawa who were relatives of Scott by his second marriage. Their memories of the man were still clear.

This is an updated, expanded edition of a book originally published in 2013. What is new for the 2024 version?

I added some details of which I was unaware when the first edition appeared—the way, for example, that Scott smoothed the way for the American novelist Sinclair Lewis to travel in northern Saskatchewan and Manitoba in 1924. (Lewis went on to write a mediocre novel, Mantrap, in which he said miserably unpleasant things about Indigenous people.) Apart from adding that kind of material, I also updated the conversations with Scott, bringing them from the Obama-Harper era to the Biden-Trudeau years. More important, I needed to take into account the massive reports of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the discovery of unmarked graves near residential schools, the Pope’s apology to Indigenous people, his renunciation of the terra nullius doctrine, and so on.

What response have you received from readers to the expanded version?

I’ve been delighted by the response so far. For example, my old mentor and friend Bob Calder—one of the most distinguished professors of English ever to teach at USask—called the work “totally absorbing” and wrote, “It’s a book that I think every Canadian (and, indeed, American) should read.” I couldn’t ask for a better recommendation.

How can books like this contribute to reconciliation in Canada?

As William Faulkner once wrote, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” There’s a lot of painful wisdom in that idea. I believe that if settler Canadians are ever going to reach true reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, we need a better sense of what went wrong in the building of our nation, and why. I hope Conversations with a Dead Man helps to build such an understanding—in a lively and readable way.

Is there anything else that you would like to add?

In writing the book, I had to guard against a risk that all biographers face: becoming too fond of the person they’re writing about. Duncan Campbell Scott was not some cardboard villain—he had many excellent qualities. I empathized with him in a number of ways. But, having said that, I could never allow myself to turn away from the lasting and terrible impact of his work as the head of Indian Affairs.